In a World of Slugworths, Be a Wonka

- dougkatz8

- Jan 30

- 3 min read

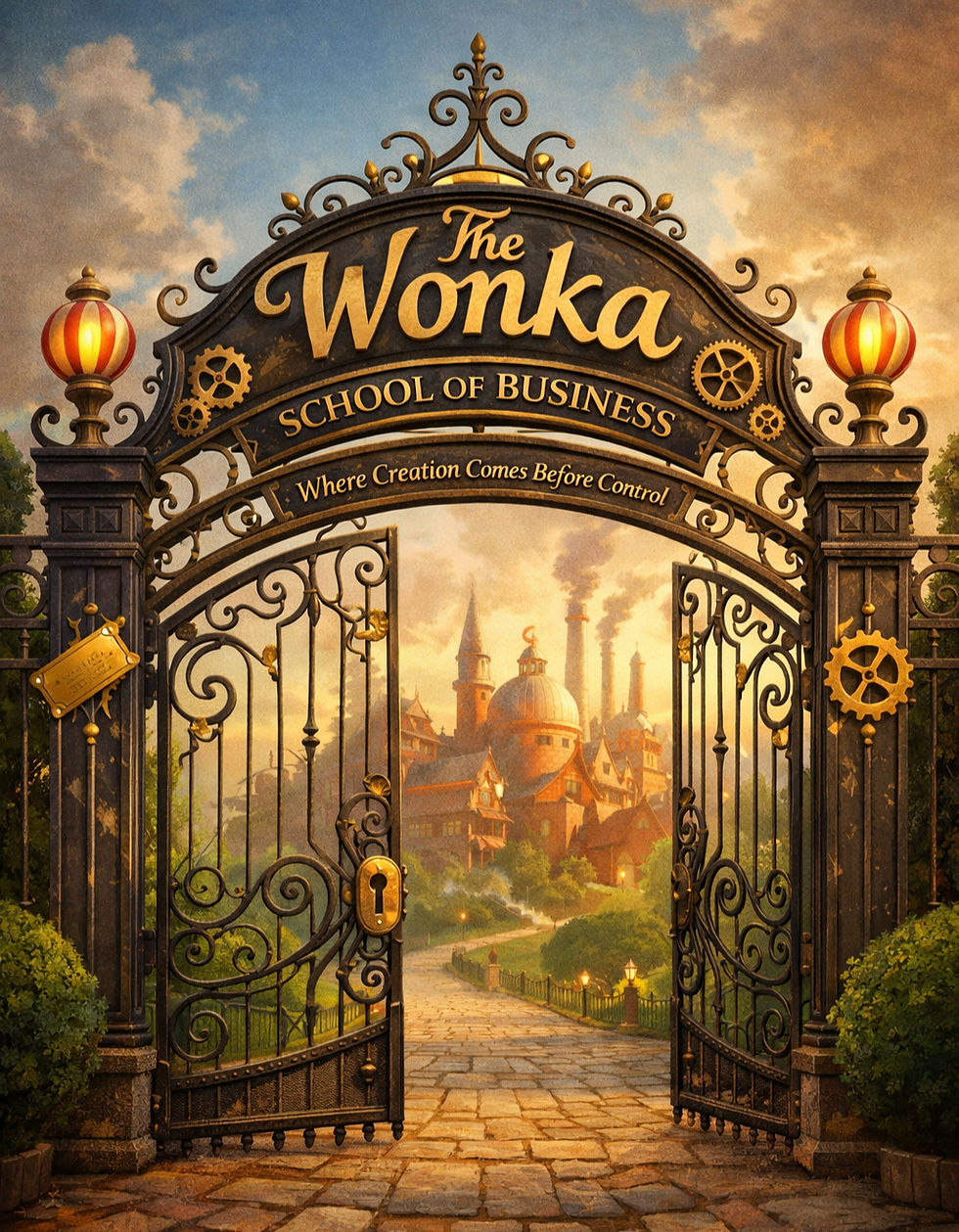

Entrepreneurial lessons from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory or making good in a wary world.

There are very few movies that feel universally beloved—not just popular or successful, but beloved. Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is one of those rare cultural touchstones. I've never met anyone who actively dislikes it. That alone should tell us something.

It isn't just nostalgia. It isn't just Gene Wilder's performance or the songs or the candy. It's what the movie says—quietly, cleverly, and without pretending to be a business lesson at all. It presents a vision of creativity, integrity, stewardship, and restraint that feels almost radical today.

Because if you look around at modern American business leadership, what you mostly see aren't Wonkas.

You see Slugworths.

The Slugworth Era

Slugworth isn't memorable because he's clever or capable. He's memorable because he represents something hollow: a fixation on extraction rather than creation. He doesn't build. He doesn't imagine. He doesn't inspire. He spies. He manipulates. He schemes. He tries to win by stealing, sabotaging, or crushing the source of real innovation instead of producing any himself.

Today's business environment is filled with leaders who mistake regulatory capture for strategy, legal dominance for innovation, and market power for merit. Product quality is secondary. Customer outcomes are negotiable. Ethics are optional as long as the quarterly numbers work.

And when actual innovation shows up—real ideas, real momentum, real disruption—the response isn't curiosity or collaboration. It's litigation. It's patent warfare. It's weaponized IP designed not to encourage invention, but to suffocate it.

The patent system, which was meant to protect creators long enough to bring ideas into the world, has been bent into a bludgeon. Entire legal departments exist not to advance technology, but to ensure that no one smaller, faster, or more imaginative survives long enough to matter.

This gets labeled "capitalism."

It isn't. It's fear with a balance sheet.

What Wonka Got Right

Willy Wonka is a strange character on the surface, but a deeply grounded one underneath. He is imaginative without being reckless. Playful without being careless. Visionary without being detached from right and wrong.

He builds things that don't exist—and then builds the systems to make them real.

Wonka doesn't race competitors. He doesn't chase trends. He doesn't copy. He creates an entire category and then refuses to dilute it. His factory isn't optimized for scale at the expense of wonder. It's optimized for possibility.

And notice something else: Wonka isn't obsessed with control for control's sake. He withdraws from the world not to dominate it, but to protect what he's building from corruption. His secrecy isn't greed—it's stewardship.

He understands something modern leaders often miss: not everything valuable should be maximized, rushed, or stripped for parts.

People Are Not Inputs

One of the most quietly subversive parts of the story is how Wonka treats labor.

The Oompa Loompas aren't exploited punchlines. They're collaborators from a different world, with different skills, culture, and rhythm. Wonka doesn't try to turn them into something else. He builds with what they already are. He doesn't optimize them. He orchestrates them.

Their presence amplifies his vision instead of threatening it.

There's a lesson there that modern business pretends to understand but rarely practices: diversity isn't cosmetic. It's functional. Great builders know they don't win by surrounding themselves with mirrors. They win by inviting in capabilities they don't possess themselves.

Wonka doesn't fear that. Slugworth does.

Charlie Is the Point

If the movie were just about invention, it would end at the factory gates.

But it doesn't. It ends with succession.

Charlie doesn't win because he's clever. He wins because he's decent. His first instinct isn't conquest—it's service. He thinks about his family. Responsibility. Whether he's worthy of what's being offered.

That's not accidental. It's the entire thesis.

Wonka understands that what he created was never truly his. He was its steward, not its owner. And stewardship implies something modern leadership desperately avoids: letting go.

Without Charlie, the factory dies with Wonka. Without mentorship, without values transfer, without intentional succession, even the greatest creations rot into brands, shells, or lawsuits.

The future isn't protected by dominance. It's protected by succession with integrity.

Be a Wonka

We don't need more Slugworths. We don't need more executives who can arbitrage regulation, out-lawyer competitors, or extract value until nothing is left.

We need builders who remember why they started. Leaders who still believe that imagination paired with discipline can change things. Entrepreneurs who understand that success isn't just scale—it's legacy.

Wonka wasn't naïve. He was precise. He wasn't chaotic. He was intentional. He didn't reject capitalism—he rejected emptiness.

In a world that rewards Slugworth behavior and calls it sophistication, choosing to be a Wonka is a deliberate act. It means building something real. Protecting it without poisoning the well. Treating people as contributors, not costs. And knowing when the most important move isn't growth—but passing the keys to someone who will care.

Comments